We Are Non Profit Organization

Founded Feb. 12. 1909, the NAACP is the nation’s oldest, largest, and most widely recognized grassroots-based civil rights organization. Its more than half-million members and supporters throughout the United States and the world are the premier advocates for civil rights in their communities, campaigning for equal opportunity and conducting voter mobilization.

For more history see our Juneteenth website Freedom Lounge.

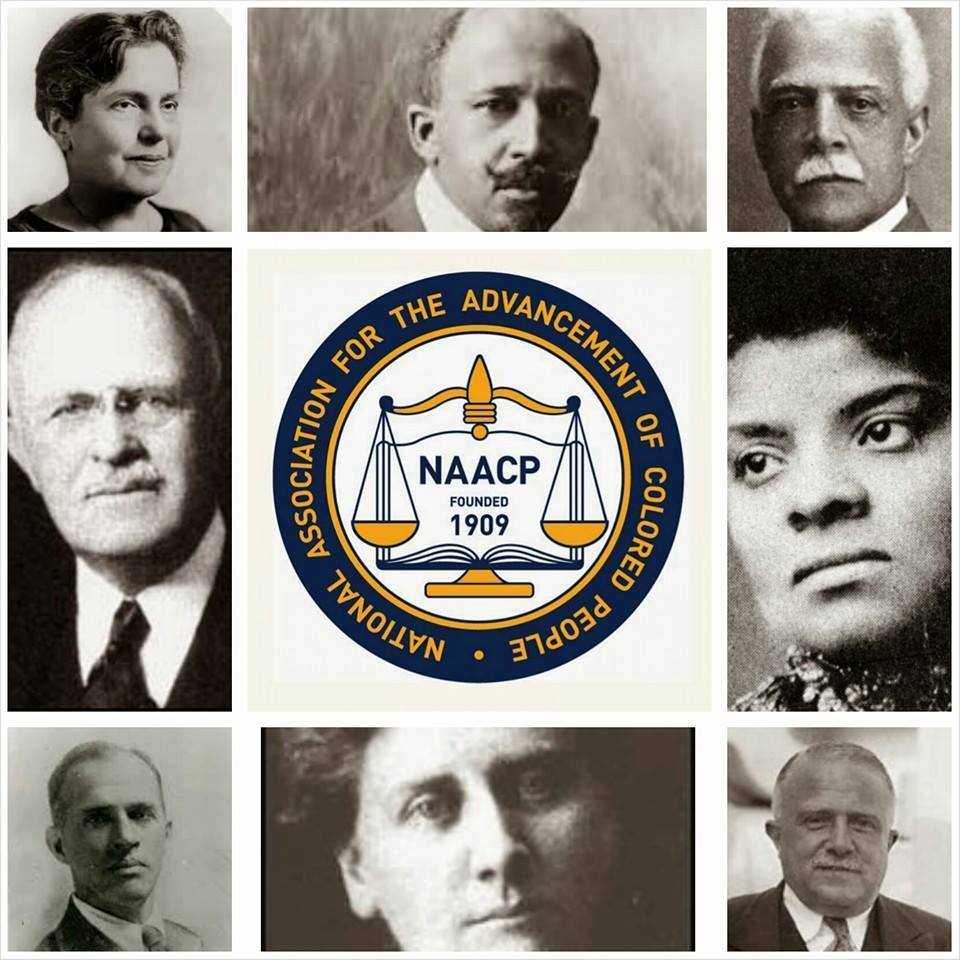

Founding Members

The NAACP was formed partly in response to the continuing horrific practice of lynching and the 1908 race riot in Springfield, the capital of Illinois and resting place of President Abraham Lincoln. Appalled at the violence that was committed against blacks, a group of white liberals that included Mary White Ovington and Oswald Garrison Villard, both the descendants of abolitionists, William English Walling and Dr. Henry Moscowitz issued a call for a meeting to discuss racial justice. Some 60 people, seven of whom were African American (including W. E. B. Du Bois, Ida B. Wells-Barnett and Mary Church Terrell), signed the call, which was released on the centennial of Lincoln’s birth.

Other early members included Joel and Arthur Spingarn, Josephine Ruffin, Mary Talbert, Inez Milholland, Jane Addams, Florence Kelley, Sophonisba Breckinridge, John Haynes Holmes, Mary McLeod Bethune, George Henry White, Charles Edward Russell, John Dewey, William Dean Howells, Lillian Wald, Charles Darrow, Lincoln Steffens, Ray Stannard Baker, Fanny Garrison Villard, and Walter Sachs.

The NAACP Seeks to Remove Barriers of Racial Discrimination

Echoing the focus of Du Bois’ Niagara Movement began in 1905, the NAACP’s stated goal was to secure for all people the rights guaranteed in the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments to the United States Constitution, which promised an end to slavery, the equal protection of the law and universal adult male suffrage, respectively.

The NAACP’s principal objective is to ensure the political, educational, social and economic equality of minority group citizens of United States and eliminate race prejudice. The NAACP seeks to remove all barriers of racial discrimination through the democratic processes.

The NAACP established its national office in New York City in 1910 and named a board of directors as well as a president, Moorfield Storey, a white constitutional lawyer and former president of the American Bar Association. The only African American among the organization’s executives, Du Bois was made director of publications and research and in 1910 established the official journal of the NAACP, The Crisis as the premier crusading voice for civil rights. Today, The Crisis, one of the oldest black periodicals in America, continues this mission. A respected journal of thought, opinion and analysis, the magazine remains the official publication of the NAACP and is the NAACP’s articulate partner in the struggle for human rights for people of color.

Growth of the Organization Across the United States

With a strong emphasis on local organizing, by 1913 the NAACP had established branch offices in such cities as Boston, Massachusetts; Baltimore, Maryland; Kansas City, Missouri; Washington, D.C.; Detroit, Michigan; and St. Louis, Missouri.

A series of early court battles, including a victory against a discriminatory Oklahoma law that regulated voting by means of a grandfather clause (Guinn v. United States, 1910), helped establish the NAACP’s importance as a legal advocate. The fledgling organization also learned to harness the power of publicity through its 1915 battle against D. W. Griffith’s inflammatory Birth of a Nation, a motion picture that perpetuated demeaning stereotypes of African Americans and glorified the Ku Klux Klan. NAACP membership grew rapidly, from around 9,000 in 1917 to around 90,000 in 1919, with more than 300 local branches.

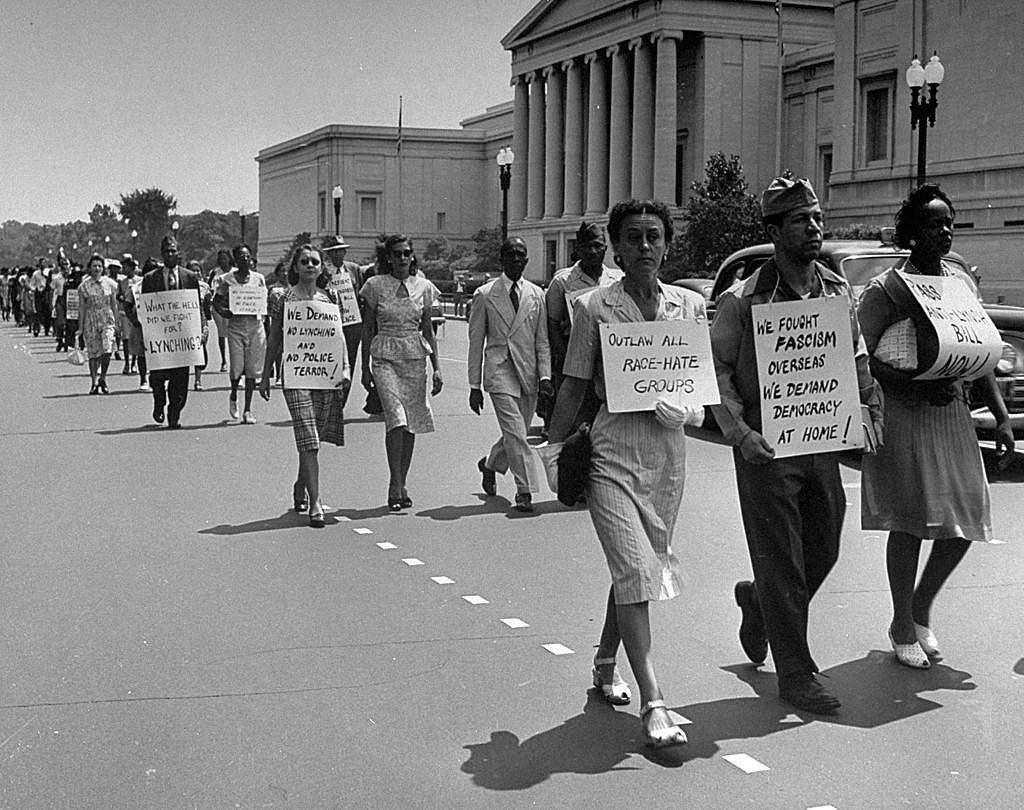

The NAACP waged a 30-year campaign against lynching, among the Association’s top priorities. After early worries about its constitutionality, the NAACP strongly supported the federal Dyer Bill, which would have punished those who participated in or failed to prosecute lynch mobs. Though the bill would pass the U.S. House of Representatives, the Senate never passed the bill, or any other anti-lynching legislation. Most credit the resulting public debate-fueled by the NAACP report “Thirty Years of Lynching in the United States, 1889-1919”-with drastically decreasing the incidence of lynching.

Johnson stepped down as secretary in 1930 and was succeeded by Walter F. White. White was instrumental not only in his research on lynching (in part because, as a very fair-skinned African American, he had been able to infiltrate white groups), but also in his successful block of segregationist Judge John J. Parker’s nomination by President Herbert Hoover to the U.S. Supreme Court.

White presided over the NAACP’s most productive period of legal advocacy. In 1930 the association commissioned the Margold Report, which became the basis for the successful reversal of the separate-but-equal doctrine that had governed public facilities since 1896’s Plessy v. Ferguson. In 1935 White recruited Charles H. Houston as NAACP chief counsel. Houston was the Howard University law school dean whose strategy on school-segregation cases paved the way for his protégé Thurgood Marshall to prevail in 1954’s Brown v. Board of Education, the decision that overturned Plessy.

During the Great Depression of the 1930s, which was disproportionately disastrous for African Americans, the NAACP began to focus on economic justice. After years of tension with white labor unions, the Association cooperated with the newly formed Congress of Industrial Organizations in an effort to win jobs for black Americans. White, a friend and adviser to First Lady–and NAACP national board member–Eleanor Roosevelt, met with her often in attempts to convince President Franklin D. Roosevelt to outlaw job discrimination in the armed forces, defense industries and the agencies spawned by Roosevelt’s New Deal legislation.

Roosevelt ultimately agreed to open thousands of jobs to black workers when labor leader A. Philip Randolph, in collaboration with the NAACP, threatened a national March on Washington movement in 1941. President Roosevelt also agreed to set up a Fair Employment Practices Committee (FEPC) to ensure compliance.

Throughout the 1940s the NAACP saw enormous growth in membership, recording roughly 600,000 members by 1946. It continued to act as a legislative and legal advocate, pushing for a federal anti-lynching law and for an end to state-mandated segregation.

The Civil Rights Era

By the 1950s the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, headed by Marshall, secured the last of these goals through Brown v. Board of Education (1954), which outlawed segregation in public schools. The NAACP’s Washington, D.C., bureau, led by lobbyist Clarence M. Mitchell Jr., helped advance not only integration of the armed forces in 1948 but also passage of the Civil Rights Acts of 1957, 1964, and 1968, as well as the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

NAACP Mississippi Field Secretary Medgar Evers was assassinated by a sniper in front of their residence following years of investigations into hostility against blacks and participation in non-violent demonstrations such as sit-ins to protest the persistence of Jim Crow segregation throughout the south.

Although it was criticized for working exclusively within the system by pursuing legislative and judicial solutions, the NAACP did provide legal representation and aid to members of other protest groups over a sustained period of time. The NAACP even posted bail for hundreds of Freedom Riders in the ‘60s who had traveled to Mississippi to register black voters and challenge Jim Crow policies.

Led by Roy Wilkins, who succeeded Walter White as secretary in 1955, the NAACP, along with A. Philip Randolph, Bayard Rustin and other national organizations began to plan the 1963 March on Washington.

With the passage of major civil rights legislation the following year, the Association accomplished what seemed an insurmountable task.

1977

Wilkins retired as executive director in 1977 and was replaced by Benjamin L. Hooks, whose tenure included the Bakke case (1978), in which a California court outlawed several aspects of affirmative action. During his tenure the Memphis native is credited with implementing many NAACP programs that continue today. The NAACP ACT-SO (Academic, Cultural, Technological and Scientific Olympics) competitions, a major youth talent and skill initiative, and Women in the NAACP began under his administration.

1992

Dr. Hooks served as executive director/chief executive officer (CEO) of the NAACP from 1977 to 1992. Benjamin F. Chavis (now Chavis Muhammad) became executive director/CEO in 1993, while in 1995 Myrlie Evers-Williams (widow of Medgar Evers) became the third woman to chair the NAACP, a position she held until 1998, succeeded by Chairman Emeritus Julian Bond.

1996

In 1996 the NAACP National Board of Directors changed the executive director/CEO title to president and CEO when it selected Kweisi Mfume, a former congressman and head of the Congressional Black Caucus, to lead the body. The elected office of president was eliminated.

2005

Former telecommunications executive Bruce S. Gordon followed in 2005. NAACP General Counsel Dennis Courtland Hayes would serve the Association well as interim national president and CEO twice during changes in administrations in recent years.

2008

In May 2008, the NAACP National Board of Directors confirmed Benjamin Todd Jealous, a former community organizer, newspaper editor and Rhodes Scholar, as the 14th national executive of the esteemed organization.

2017

Derrick Johnson was unanimously elected president & CEO of the NAACP. A Detroit native now residing in Jackson, Mississippi, Mr. Johnson is a longtime member, leader, and a respected veteran activist who will be tasked with guiding the NAACP through a period of tremendous challenge and opportunity at a key point in its 108-year history. The NAACP has undergone transitions in leadership this year as it re-envisions itself to take on a tumultuous and contentious social and political climate. He will have a three-year term.

Civil Rights Leaders